Umber’s roots

Alongside other earth pigments (red, yellow and black ochres, and calcite white) raw umber is found in a natural state, mixed with rudimentary binders and then painted. The earliest examples date back to Palaeolithic cave paintings, including the well-preserved examples of animals and cattle painted in Lascaux in southwestern France around 17,000 years ago.

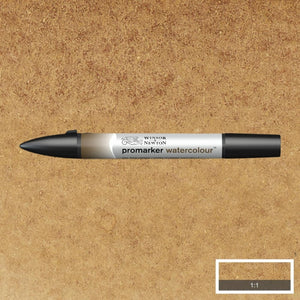

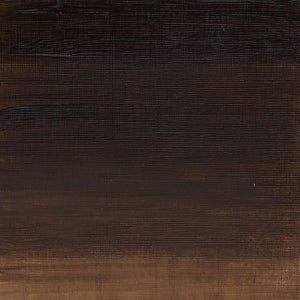

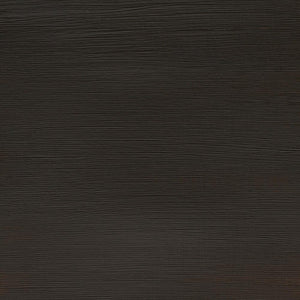

When found in its natural form, umber is referred to as ‘raw umber’ and when heated to high temperatures it is a deep-red ‘burnt umber’. The same natural sources that raw umber is composed of – iron oxide, manganese and aluminium silicate – are found in many parts of the world. The finest grade, however, is said to originate from Cyprus, but it was in Italy that umber was first sourced commercially.

There are two theories behind the origins of umbra’s name. One refers to Umbria, the mountainous region in central Italy where it was first extracted in the 15th century. The other concerns the painting of shadows. Much like the word ‘umbrella’, with which it shares the Latin term for ‘shadow’.

Earthy palettes

The medieval palette favoured a brighter spectrum of colour combinations, from bright azurite blue to bold cinnabar red and striking verdigris green. Later, during the Renaissance, artists began to paint more naturalistic scenes than the graphic images typical of medieval painting. It was time to bring the earthiness of umber and sienna back into the fold. Dutch master Hieronymus Bosch, for example, introduced raw umber in the shadows of his famous triptych ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’ (1490–1500).

Creating light and shadow

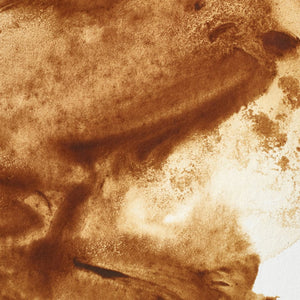

Raw umber’s greatest association with the use of shadows is found in the Baroque ‘chiaroscuro’ style of painting. The Italian term describes the extreme contrast between light and dark. This visual technique champions the art of extremes in dramatic effect, usually with a bright light shining on a figure and a dark background from which they emerge.

But why use a dark brown pigment instead of black? Raw umber became a more attractive alternative to black in shadows because it provides a warmer, less harsh shadow. It is semi-opaque, very lightfast and popular for underpainting because it dries so quickly. We can see this choice in the background of Vermeer’s ‘The Milkmaid’ (1650) in which a semi-transparent brown is applied to the background’s wall to provide a warmer, more natural-looking shadow. Other artists who used this technique include Caravaggio, in ‘Supper at Emmaus’ (1601) and Rembrandt, in ‘Self-portrait as the Apostle Paul’ (1661).

Changes in popularity

Raw umber’s popularity decreased during the 19th century, as the Impressionists developed different approaches to the painting of shadows. Artists such as Monet adopted elements from the relatively new theory of complementary colours. For example, violet was used to create shadows against its complementary colour of yellow, the colour of sunlight.

Other shadowy palettes and brown tones were made from mixtures of red, yellow, green and blue in combination with new synthetic pigments such as cobalt blue and emerald green. In later years the impact of this shift is described by Salvador Dali, as he discusses his aversion to raw umber in his book 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship (1948).

Despite these fluctuations, raw umber is still a versatile colour that continues to be a favourite in many painters’ palettes. Today, it is used as a subtle, warm and grounding colour, perfect for natural landscapes, underpainting, monochromatic pieces and the depiction of shadows inspired by its name.

![WN PWC KAREN KLUGLEIN BOTANICAL SET [OPEN 3]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/136448.jpg?crop=center&v=1761625362&width=20)

![WN PWC KAREN KLUGLEIN BOTANICAL SET [FRONT]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/136444.jpg?crop=center&v=1761625362&width=20)

![WN PWC ESSENTIAL SET [CONTENTS 2]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/137579.jpg?crop=center&v=1761625558&width=20)

![WN PWC ESSENTIAL SET [FRONT]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/137583.jpg?crop=center&v=1761625558&width=20)

![W&N GALERIA CARDBOARD SET 10X12ML 884955097809 [OPEN]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/138856.jpg?crop=center&v=1761626083&width=20)

![W&N GALERIA CARDBOARD SET 10X12ML [B014096] 884955097809 [FOP]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/138855.jpg?crop=center&v=1761626083&width=20)

![W&N PROMARKER 24PC STUDENT DESIGNER 884955043295 [OPEN]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/78675_d6356b09-bd48-4280-8df1-eefc85a4de3b.jpg?crop=center&v=1761841229&width=20)

![W&N PROMARKER 24PC STUDENT DESIGNER 884955043295 [FRONT]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/78674_d4d78a69-7150-4bf4-a504-3cb5304b0f80.jpg?crop=center&v=1721326116&width=20)

![W&N PROFESSIONAL WATER COLOUR TYRIAN PURPLE [SWATCH]](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/136113.jpg?crop=center&v=1724423390&width=20)

![W&N WINTON OIL COLOUR [COMPOSITE] 37ML TITANIUM WHITE 094376711653](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/9238_5073745e-fcfe-4fad-aab4-d631b84e4491.jpg?crop=center&v=1721326117&width=20)

![W&N WINTON OIL COLOUR [SPLODGE] TITANIUM WHITE](http://www.winsornewton.com/cdn/shop/files/131754_19b392ee-9bf6-4caf-a2eb-0356ec1c660a.jpg?crop=center&v=1721326118&width=20)